Student Blog: Matt Haller

Third year student Matt Haller writes about film history and the cinematic influences on his second year film in this student blog.

Photo credit: Berlin Segovia

In my second-year at SVA, I made my most personal film, You Will Find Love.

The story is one that is incredibly important and meaningful to me and I am so happy to share it with the world. I wrote this script based on my own mental health struggles with internalized homophobia, and long regretting past loves that I never sought out because of that, but now I see a brighter future of happiness and acceptance. But the film being personal is not solely based on my life relation to it, but my relationship with cinema. The films I make are based on my encyclopedic brain of art and cinema. Every decision I make in a film I can relate back to an inspiration. In this piece, I want to catalog my influences and bring you inside my mind while making You Will Find Love and understand my creative process artistically.

First and foremost, I couldn’t have made this film–or made any film for that matter–without the cinematic gifts of Terence Davies. As I was developing the idea for this film, when it was still a dry seed without soil or water, I learned that Terence had passed. He introduced me to a language of cinema that was virgin to my senses when I saw The Long Day Closes for the first time in the Spring of 2021. He gave me the confidence to tell stories that I hold close to my chest and open up my life to the world, and feel accepted in that vein. As much as I made this film for me and for other queer individuals like myself, I made this film for him.

Still from The Long Day Closes (1992)

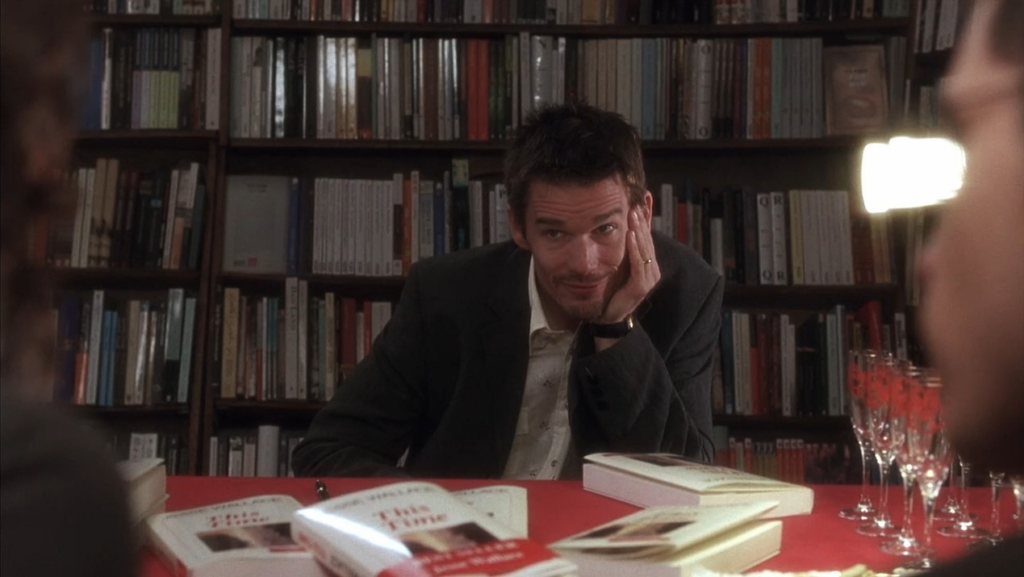

The film opens on a wooded scene with two young men sitting on a log.

This is a glimpse into the book of Simon, our main character, that we pull out of and realize he is reading to an audience inside a bookstore. I wanted this opening to be really the only sign of green within the film, to make it unique, and I wanted a mint green like the orchard in Weerasethakul’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives or the decaying old mansion in Victor Erice’s recent masterpiece Close Your Eyes. In contrast, when we dissolve into the bookstore, we are assaulted with warm colors of red, orange, and brown to contrast the mint green.

I took inspiration from the cozy feeling of the bookstores within Linklater’s Before Sunset and Joan Micklin Silver’s Crossing Delancey. Speaking of Delancey Street, we shot this scene a few blocks away on Orchard Street at a bookstore called P&T Knitwear. I had been in the store a number of times, having written some parts of the film there, and fell in love with the atmosphere.

My favorite shot in this scene is the close-up of Simon from behind, as he leans his head down away from the crowd. I was inspired compositionally by Welles’ framing of faces in Chimes at Midnight, and how he uses the space around them to heighten the emotion. We do not see Simon’s face, but the surrounding negative space of the out-of-focus crowd creates an isolating feeling that I wanted to implant on the character, not just feeling trapped in what he considers sub-par work but the vacancy in his life as a whole. The shot later in the scene with Gabriel from behind came from TÁR, the first time we see the mystery woman from behind at Lincoln Center.

Still from Before Sunset (2004)

I took heavy inspiration from classic romance melodramas that play your heartstrings like a harp;

specifically Carl Dreyer’s Gertrud and Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows. The majority of this film takes place in one room, so it was important for me to understand how to use the space and make it feel whole. Most of Dreyer’s swan song is conversations in rooms, like my film, but his camera movements and lighting techniques assault the viewer with so much visual language. It was important for me to not allow this conversation to become a “play”, but always have it continuously cinematic.

I also studied the paintings of Johannes Vermeer and Vilhelm Hammershøi, who frame their subjects in a way that not only leaves room to breathe but lets their process command the story of the artwork. There’s a sensual loneliness to both their works that I wanted to capture in the frame. I love the stillness and soft atmosphere of Hammershoi’s work and I love the distance and restraint in Vermeer. I imagine without Gabriel there, Simon’s apartment feels like a Hammershoi painting–and in fact, I modeled the shot early on with Simon at his computer after ‘Interior in Strandgade, Sunlight on the Floor’.

Essentially, I wanted to allow the actors space and breathe. In rehearsals, I saw Simon Henriques (Gabriel) light up as I instructed him on how to use the setting to his advantage. When both he and Henry Truitt Harshaw (Simon) entered, Henriques completely took over making himself at home in a place unfamiliar to him. It was pure magic, and I knew there was such strength in his physical performance from that.

Vilhelm Hammershøi, Interior in Strandgade, Sunlight on the Floor, 1901

The pacing was essential for me when constructing the apartment dialogue.

Since it’s the majority of the film, I knew that the pattern of the edit was essential to get down. I love any dialogue between Hester and Freddie in The Deep Blue Sea. What inspires me so much about that is how Terence always focuses on the speaker as they deliver their lines. I didn’t want to J-cut too much because I felt what would create the emotion was not action but action and reaction; how a line is spoken and how the other character takes in that information. I also love the diner scene in Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight and the interview in Ferrara’s Pasolini.

In editing, no film was more vital than Sidney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon.

The scene where Sonny is delivering his final will and testament is composed of only four shots, in a four-minute scene; a wide, a close-up, and two reaction shots. There is no other coverage necessary because what matters isn’t the coverage but the performance. That was what was most important to me as well, not getting all the coverage into the picture (there are some shots we got that are absent) but capturing the best performances from both actors. Henry put so much emotion into that scene, you could feel it in the room before the cameras were rolling and after we called cut. To me, really finding the heart of those two performances was my primary goal. I’m so proud of both Henry and Simon. I love them so much, both as performers and people.

After the final moments of their conversation is when we have the “money shot,” the time elapsing afternoon-to-evening dolly shot. This and the film’s closing moments (which I shall not spoil) I just felt in my bones I wanted in this film. Logistically it is impractical, but I knew emotionally this was essential, and that to me is what makes a cinematic experience stick, when it has a stronger effect on your heart than your mind. Bresson says this in his classic quote, “I’d rather people feel a film before understanding it.” I envisioned it as a mixture of the rug sequence in The Long Day Closes with the log cabin lighting of All That Heaven Allows.

Director of photography Isabella Meilan and gaffer Nadia Santo helped bring this vision to life.

I brought Isa onto the project as soon as Abigail Marshall, who would become the production designer, shared that no one cares more about how the story relates to the images created than Isa. And Nadia is such a visionary talent and dedicated film worker. With them and the entire camera and electric team, they were able to create such a beautiful sequence that I am so proud of. I really owe it all to them and I hope I have made it clear how much their talent and spirits mean to me.

Still from All That Heaven Allows (1955)

We are now submitting it to festivals,

I am happy to have been given this wonderful opportunity to discuss my influences for You Will Find Love. The entire cast and crew put their heart and souls into this project. I knew Henry Truitt Harshaw and Simon Henriques were these characters from their first reading together. Pranavi Davuluri, my fearless producer, has been my champion since day one. Isa Meilan is more of a dreammaker than a cameraperson, and my editor Taylor Turgeon stepped in and made this into the extraordinary work it is. Everyone involved in the cast and crew helped bring this film to life. I could not have asked for a better team to make this film with and I share it with all of them.

Photo credit: Berlin Segovia

Poster by Ayesha Nusrath