Student Blog: Matt Haller

Third year student Matt Haller attended the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center last month, watching sixteen films over three weeks. Here, Matt writes a student blog reviewing every film he watched at the festival.

SVA BFA Film was a sponsor of New York Film Festival 62.

MATT HALLER: NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL JOURNAL

The New York Film Festival consists of some of the best films world cinema has to offer each year. The 62nd edition of the festival was no different, highlighting staples of the festival circuit and films with American premieres. I was honored to have been able to cover the festival for the School of Visual Arts film department, discovering another strong year for one of the most consistently strong festivals across the globe.

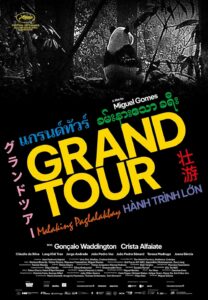

GRAND TOUR (Miguel Gomes, 128m):

Miguel Gomes presents a film at the midpoint between Werner Herzog and Chris Marker. The story is of a couple in the late 1910’s traveling through various East Asian countries, one trying to escape the other as to not marry. At the heart is Gomes’ fascination with nature and culture, and the intersection of the two. Being in this midpoint creates issues, though. In films like Aguirre, the Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo, Herzog constructs a novelistic story with a strong active protagonist, showcasing the evils of colonialism. Marker’s cinema, like in Sans Soleil, is direct and represents the world he wants to show the audience at face value. The story of Grand Tour is not strong enough to lead the audience along, forming a strange blend of narrative and documentary that never truly works.

Miguel Gomes presents a film at the midpoint between Werner Herzog and Chris Marker. The story is of a couple in the late 1910’s traveling through various East Asian countries, one trying to escape the other as to not marry. At the heart is Gomes’ fascination with nature and culture, and the intersection of the two. Being in this midpoint creates issues, though. In films like Aguirre, the Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo, Herzog constructs a novelistic story with a strong active protagonist, showcasing the evils of colonialism. Marker’s cinema, like in Sans Soleil, is direct and represents the world he wants to show the audience at face value. The story of Grand Tour is not strong enough to lead the audience along, forming a strange blend of narrative and documentary that never truly works.

Admittedly, I do think Grand Tour won me over in the end. The film is split into two parts. In the first part, following the character Edward, Gomes’ verite is at its strongest, with incredible sequences like the Blue Danube Waltz sequence or a really tender moment as a man breaks down in tears singing My Way. In the second part, with the character Molly, the story is at its strongest, reminding me of a classic Renoir. I believe scene by scene Grand Tour is a strong film, but as one piece it does not work.

SCÉNARIOS + EXPOSÉ DU FILM ANNONCE DU FILM “SCÉNARIO” (Jean-Luc Godard, 53m):

Last year, I was at the premiere of Godard’s first posthumous film, Trailer for a Film That Will Never Be Made “Phony Wars”. It was one of the most moving experiences I have had seeing a film. Inside the Debussy Cinema at the Cannes Film Festival, assaulted by the note cards and operatic musical interludes, I was transfixed. It is a beautiful farewell to a career or redefining the art of cinema for six decades. Scénarios, the “new” final Godard film, is his last cinematic statement, the last film he ever completed. To me Scénarios feels like when The Beatles released Abbey Road before Let It Be. Scénarios plays like Godard’s usual output from the past two decades, and though it is no less elliptical and introspective it does not stick out as unique in regards to the rest of his recent work. The film is a glimpse into violence in cinema. Perhaps this is what Godard wanted to end his career with, but it does not stand as emotionally raw and cinematically bold as his previous posthumous film.

Last year, I was at the premiere of Godard’s first posthumous film, Trailer for a Film That Will Never Be Made “Phony Wars”. It was one of the most moving experiences I have had seeing a film. Inside the Debussy Cinema at the Cannes Film Festival, assaulted by the note cards and operatic musical interludes, I was transfixed. It is a beautiful farewell to a career or redefining the art of cinema for six decades. Scénarios, the “new” final Godard film, is his last cinematic statement, the last film he ever completed. To me Scénarios feels like when The Beatles released Abbey Road before Let It Be. Scénarios plays like Godard’s usual output from the past two decades, and though it is no less elliptical and introspective it does not stick out as unique in regards to the rest of his recent work. The film is a glimpse into violence in cinema. Perhaps this is what Godard wanted to end his career with, but it does not stand as emotionally raw and cinematically bold as his previous posthumous film.

Following Scénarios same Exposé du film annonce du film “Scénario”, a 36 minute unbroken take[sic] of Godard explaining a film that truly will never be made. I believe the intent was for his collaborators to finish the film for him. Instead, they decided to leave the film as is and not attempt to recreate his vision. It is fascinating to go inside the mind of Godard and understand his artistic perspective.

The idea of the Image Book is seen directly in this, as we look at the book of this film, much like the pages seen in “Phony Wars”, but for a film that Godard was never able to complete. There are sketches, pictures, film references, names of composers, oil paintings, etc. Exposé du film annonce du film “Scénario” plays wonderfully as an addendum to Mitra Farahani’s extraordinary See You Friday, Robinson; one is a portrait of an artist, the other a portrait of an artist as a man.

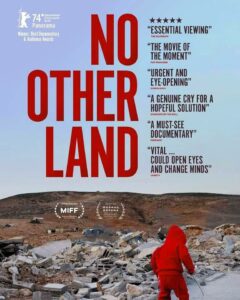

NO OTHER LAND (Various, 95m):

I remember when a few months into the genocide in Gaza, a close friend asked me why there was no modern Groupe Dziga Vertov; Godard’s political filmmaking collective in the last 60’s and 70’s. Why are there no filmmakers going into the heart of Gaza and documenting the horrors? It is a fair point, but my response to him was the mere question of why we would need a Groupe Dziga Vertov in the age of the cell phone. We’ve seen journalists like Motaz Azaiza and Bisan Owda (who recently won an Emmy for her work) using compact cameras, iPhones, and TikTok to present their verite perspective.

I remember when a few months into the genocide in Gaza, a close friend asked me why there was no modern Groupe Dziga Vertov; Godard’s political filmmaking collective in the last 60’s and 70’s. Why are there no filmmakers going into the heart of Gaza and documenting the horrors? It is a fair point, but my response to him was the mere question of why we would need a Groupe Dziga Vertov in the age of the cell phone. We’ve seen journalists like Motaz Azaiza and Bisan Owda (who recently won an Emmy for her work) using compact cameras, iPhones, and TikTok to present their verite perspective.

Now we have No Other Land, by a Palestinian filmmaking collective consisting of Basel Adra, Yuval Abraham, Hamdan Ballal, and Rachel Szor; which showcases Israel’s illegal occupation of the West Bank through direct cinema. Shot in the years leading up to October 7th, the collective catalogs Israel’s destruction of their native village; demolishing homes, paralyzing citizens, and in the end desecrating the village’s only school. The filmmakers shoot on their camcorders and cell phones, providing the most singular and direct view of these events. The film captures the people, and how much the occupation affects a community; as well how political activism affects the individual. This is the most important document of the illegal occupation we have presently, and what Adra and his team achieved is immense.

A REAL PAIN (Jesse Eisenberg, 90m):

If you had told me that one of my favorite films of the New York Film Festival would be Planes, Trains, and Automobiles meets The Zone of Interest, I would not have believed you. But alas, Eisenberg in his sophomore feature achieves a synthesis of humor and pathos so pure and whole. It is a feat impressive for any filmmaker. Much like Linklater’s Hit Man from earlier this year, it takes a retired film structure and molds it into a reflection on generational trauma and family ties.

If you had told me that one of my favorite films of the New York Film Festival would be Planes, Trains, and Automobiles meets The Zone of Interest, I would not have believed you. But alas, Eisenberg in his sophomore feature achieves a synthesis of humor and pathos so pure and whole. It is a feat impressive for any filmmaker. Much like Linklater’s Hit Man from earlier this year, it takes a retired film structure and molds it into a reflection on generational trauma and family ties.

I acknowledge that I am the direct audience for this film. I come from both Holocaust survivors and “Mayflower Jews” as the movie says (off the boat European Jews pre-WWII). On top of that Eisenberg and Culkin, playing cousins David and Benji, bring back memories of my sister and I growing up. The love and tension; it is all there. I am more emotionally closed off, whereas my sister is more emotionally open yet erratic. This creates a rift between the two but also a concern for each other. Eisenberg and Culkin embody these characters effortlessly, Culkin specifically giving a performance that exceeds many of the best of the year.

Form is not lost on Eisenberg in this film either. Like Glazer with The Zone of Interest, he approaches the horrors of the Holocaust and the locations surrounding the camps with an observational distance. We as audience members become a tourist along with David and Benji, using wide angle lenses to view Poland in a matter-of-fact directness. Tighter lenses are used when focusing on the characters outside these settings. A Real Pain presents itself as a classic duo comedy, but holds so much richness in character and form. It is a brilliant film that I hope is not forgotten in time.

ALL WE IMAGINE AS LIGHT (Payal Kapadia, 118m):

The sensual cinema film of the year comes in the form of Payal Kapadia’s new feature film, about two nurses who are navigating their love lives. The older of the two’s husband has been in Germany for the past two years, and she is alone, aching for some form of love in her life. The younger is in love with a Muslim man, and is hiding their love from their families. Half in the city of Mumbai, half in a beach town, the film is an exquisite journey of love, longing, and passion. It is not hard to fall in love with Kapadia’s film, and I found it profoundly moving.

The sensual cinema film of the year comes in the form of Payal Kapadia’s new feature film, about two nurses who are navigating their love lives. The older of the two’s husband has been in Germany for the past two years, and she is alone, aching for some form of love in her life. The younger is in love with a Muslim man, and is hiding their love from their families. Half in the city of Mumbai, half in a beach town, the film is an exquisite journey of love, longing, and passion. It is not hard to fall in love with Kapadia’s film, and I found it profoundly moving.

THE SUIT (Heinz Emigholz, 90m):

I must admit I walked out of The Suit. I went in with interest, having never heard of the director before, and at first was caught up in the film’s atmosphere. You could call The Suit a comedic take on late Straub, featuring long monologues of singular characters that breaks down the form; notably here featuring ten or so different angles of coverage in each scene, cutting to a different one almost every sentence. But the joke began to prune around the thirty minute mark as the monologues grew more and more pointless, and I fell out of the film’s spell. It is a unique cinematic expression with a wonderfully dry humor, but it does little to keep the audience with the film for more than half its runtime.

I must admit I walked out of The Suit. I went in with interest, having never heard of the director before, and at first was caught up in the film’s atmosphere. You could call The Suit a comedic take on late Straub, featuring long monologues of singular characters that breaks down the form; notably here featuring ten or so different angles of coverage in each scene, cutting to a different one almost every sentence. But the joke began to prune around the thirty minute mark as the monologues grew more and more pointless, and I fell out of the film’s spell. It is a unique cinematic expression with a wonderfully dry humor, but it does little to keep the audience with the film for more than half its runtime.

A TRAVELER’S NEEDS (Hong Sang-soo, 90m):

For the fourth year in a row, Hong Sang-soo has two feature films in the mainslate of the New York Film Festival, and I saw one of them. I regret missing By the Stream starring his partner Kim Min-hee, as from what I’ve heard it is one of his best films in recent years. Instead, I saw A Traveler’s Needs starring Isabelle Huppert.

For the fourth year in a row, Hong Sang-soo has two feature films in the mainslate of the New York Film Festival, and I saw one of them. I regret missing By the Stream starring his partner Kim Min-hee, as from what I’ve heard it is one of his best films in recent years. Instead, I saw A Traveler’s Needs starring Isabelle Huppert.

Working again with Hong for the third time, Huppert embodies a French tourist in Korea teaching French, with the film predominantly in English. Though not one of Hong’s strongest films this decade, it is one of his funniest, featuring some incredible character moments. I specifically love the scenes involving Huppert and Hong regulars Kwon Hae-hyo and Lee Hye-young, which is Hong at his comedic best. It is not as audacious as In Water nor is it as personal as In Our Day–or both as in The Novelist’s Film–but it is still an amusing film from the Korean minimalist master.

ANORA (Sean Baker, 139m):

Sean Baker’s Anora has hit the cultural zeitgeist in such a strong way. I have not seen such a film like Anora anticipated in the way it has in a long time. It is heartwarming to see Anora live up to the hype. It is an incredible achievement from Baker and his team; a chaotic thrill ride as anxiety-filled yet heartbreaking as the Safdie Brothers’ Uncut Gems. Like Uncut Gems with the Safdies, Anora does lose the indie spirit that made Baker’s previous films so effervescently pure. I don’t think this is a bad thing though, as it is the natural transition point for Baker and his filmmaking.

Sean Baker’s Anora has hit the cultural zeitgeist in such a strong way. I have not seen such a film like Anora anticipated in the way it has in a long time. It is heartwarming to see Anora live up to the hype. It is an incredible achievement from Baker and his team; a chaotic thrill ride as anxiety-filled yet heartbreaking as the Safdie Brothers’ Uncut Gems. Like Uncut Gems with the Safdies, Anora does lose the indie spirit that made Baker’s previous films so effervescently pure. I don’t think this is a bad thing though, as it is the natural transition point for Baker and his filmmaking.

Critics of the film have doubted the protagonist Ani. There have been criticisms over her intelligence, claiming that Baker treats her as ignorant and dumb. But truth be told, I don’t think these critics have ever been in love. When in love, we blind ourselves to the red flags within the people we love. Ani is smart, but her love for Ivan outweighs her intellect. Sean Baker is not treating Ani as dumb, he’s treating Ani as human; and understanding the human condition and our flaws is what Baker knows best.

HELLRAISER (Clive Barker, 94m):

It was great to end a five film day at the New York Film Festival with the brand new restoration of Clive Barker’s Hellraiser. I had never seen Hellraiser before, and like most in going back to this classic horror film I was shocked to find it was nothing like I expected. I prefer the works of Carpenter, Cronenberg, Craven, etc. when it comes to this era of body horror, but there is no denying the outrageous spectacle and joyride that is Hellraiser. It gets the blood flowing and pulsates your heart to dangerous BPMs. Hellraiser was the perfect way to end the night at NYFF.

It was great to end a five film day at the New York Film Festival with the brand new restoration of Clive Barker’s Hellraiser. I had never seen Hellraiser before, and like most in going back to this classic horror film I was shocked to find it was nothing like I expected. I prefer the works of Carpenter, Cronenberg, Craven, etc. when it comes to this era of body horror, but there is no denying the outrageous spectacle and joyride that is Hellraiser. It gets the blood flowing and pulsates your heart to dangerous BPMs. Hellraiser was the perfect way to end the night at NYFF.

RUMOURS (Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson, & Galen Johnson; 109m):

“Maddin at his most conventional” they call it. “A weaker Guy Maddin film” they say. Well I for one had a great time. I need time, and probably another watch, to reflect on if the film is incredibly smart or ridiculously dumb, but I must say I found it very amusing. Taking seven world leaders and putting them in a zombie survival situation tickled all my interactive nerves. I thought Rumours was absolutely hilarious and for “conventional Guy Maddin” still incredibly unique visually. A great time at the movies and maybe the first Biden parody (portrayed by Charles Dance with no American accent) to play in major cinemas.

“Maddin at his most conventional” they call it. “A weaker Guy Maddin film” they say. Well I for one had a great time. I need time, and probably another watch, to reflect on if the film is incredibly smart or ridiculously dumb, but I must say I found it very amusing. Taking seven world leaders and putting them in a zombie survival situation tickled all my interactive nerves. I thought Rumours was absolutely hilarious and for “conventional Guy Maddin” still incredibly unique visually. A great time at the movies and maybe the first Biden parody (portrayed by Charles Dance with no American accent) to play in major cinemas.

DAHOMEY (Mati Diop, 68m):

At its heart, Dahomey is two things: a political conversation and a ghost story. It documents the twenty-six works of African art being returned to the present day Republic of Benin from France, stolen under French colonialism. Diop presents a direct and fascinating document of the process of these works being returned and the debates around the return of this art. In the latter half of the film, students argue whether the return is a good thing for Benin or not. It’s fascinating because from western eyes all points made are valid; no argument is a bad opinion on the return of the art. That is what makes Dahomey so strong. The questions it lingers; as well as the haunting effect of colonialism and the identity ripped away by Western culture, not just on the population of Benin but also the artworks themselves.

At its heart, Dahomey is two things: a political conversation and a ghost story. It documents the twenty-six works of African art being returned to the present day Republic of Benin from France, stolen under French colonialism. Diop presents a direct and fascinating document of the process of these works being returned and the debates around the return of this art. In the latter half of the film, students argue whether the return is a good thing for Benin or not. It’s fascinating because from western eyes all points made are valid; no argument is a bad opinion on the return of the art. That is what makes Dahomey so strong. The questions it lingers; as well as the haunting effect of colonialism and the identity ripped away by Western culture, not just on the population of Benin but also the artworks themselves.

ON BECOMING A GUINEA FOWL (Rungano Nyoni, 95m):

Zambian filmmaker Rungano Nyoni’s newest films seems to have won over many for its powerful message of conservative culture destroying lives and the trauma left by sexual violence–both messages needed to be heard. But like last year’s Un Certain Regard success story, How to Have Sex, I found myself at a distance from this feature. Mostly because I found its style got in the way of its narrative and the structure of the film is not strong enough to carry the characters, all coming to a conclusion that does not feel like any sort of conclusion. It is a shame that a film with an important message to be presented fails to work; but alas I am in the minority.

Zambian filmmaker Rungano Nyoni’s newest films seems to have won over many for its powerful message of conservative culture destroying lives and the trauma left by sexual violence–both messages needed to be heard. But like last year’s Un Certain Regard success story, How to Have Sex, I found myself at a distance from this feature. Mostly because I found its style got in the way of its narrative and the structure of the film is not strong enough to carry the characters, all coming to a conclusion that does not feel like any sort of conclusion. It is a shame that a film with an important message to be presented fails to work; but alas I am in the minority.

PAVEMENTS (Alex Ross Perry, 128m):

If there is one thing Alex Ross Perry knows how to use well it is the talents of his collaborators in this ambitious documentary project. Teaming up with Robert Greene and Robert Kolodny, who in working together and on their own individual projects (Procession, Kate Plays Christine, The Featherweight) have towed the line between documentary and fiction the best anyone has since Kiarostami. Pavements combines concert, musical theater, cinema, and art exhibition to commemorate the legacy of the alternative 90’s group Pavement. With a film dedicated to Pavement and its own internal logic it seems difficult and abrasive on the surface, but Ross Perry has developed with Pavement and his collaborators such a warm and inviting film. I had never listened to anything by Pavement before viewing this film; now I am hooked. I doubt my experience is singular.

If there is one thing Alex Ross Perry knows how to use well it is the talents of his collaborators in this ambitious documentary project. Teaming up with Robert Greene and Robert Kolodny, who in working together and on their own individual projects (Procession, Kate Plays Christine, The Featherweight) have towed the line between documentary and fiction the best anyone has since Kiarostami. Pavements combines concert, musical theater, cinema, and art exhibition to commemorate the legacy of the alternative 90’s group Pavement. With a film dedicated to Pavement and its own internal logic it seems difficult and abrasive on the surface, but Ross Perry has developed with Pavement and his collaborators such a warm and inviting film. I had never listened to anything by Pavement before viewing this film; now I am hooked. I doubt my experience is singular.

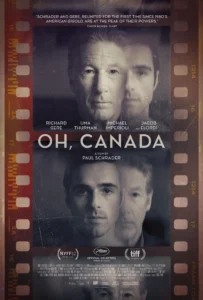

OH, CANADA (Paul Schrader, 95m):

Some jumped off the wagon after The Card Counter, others after Master Gardener; but since his comeback with First Reformed in 2018 I have remained a devotee of Paul Schrader. Though much of his late work is flawed, I can’t help but find the form entrancing and his characters deeply moving. My view has not shifted after Schrader’s new feature film Oh, Canada which I found to be a profound exploration of mortality and the myth of the ‘great artist’.

Some jumped off the wagon after The Card Counter, others after Master Gardener; but since his comeback with First Reformed in 2018 I have remained a devotee of Paul Schrader. Though much of his late work is flawed, I can’t help but find the form entrancing and his characters deeply moving. My view has not shifted after Schrader’s new feature film Oh, Canada which I found to be a profound exploration of mortality and the myth of the ‘great artist’.

Documentary filmmaker Leonard Fife (Richard Gere) gives his final testimony to his wife (Uma Thurman) and a former student of his (Michael Imperioli) on the day of his death. The film traverses through his life featuring flashbacks with him played by Jacob Elordi, and sometimes featuring Gere himself. These are flashbacks within the mind of a decaying man.

Information doesn’t add up, characters are played by recurring actors or characters meant to be young are played by their present day actors, and the tone is inconsistent. Yet it is all done with true craftsmanship from Schrader. The world of the film crumbles around us as Fife’s life comes to an end, and we feel his regret as he confesses his flaws, while also criticizing him for the character flaws he never owns up to. It is a film not too different from The Father from a few years back. Oh, Canada is a beautiful film that audiences and critics alike are unjustly slamming for the reasons that make the film so poignant.

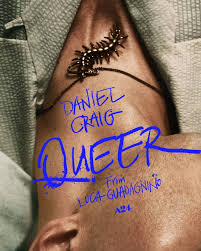

QUEER (Luca Guadagnino, 137m):

In 2017, Luca Guadagnino released Call Me By Your Name, a tremendous queer love story that would go on to be one of the most appraised films of the year and would win writer James Ivory his first Oscar. To follow this, Guadagnino would release Suspiria, a remake of the Argento horror classic that is an hour longer and expands the story and the body horror to exponential proportions. It was incredibly divisive and controversial, a bold follow-up unexpected of someone who previously directed a best picture nominated film.

In 2017, Luca Guadagnino released Call Me By Your Name, a tremendous queer love story that would go on to be one of the most appraised films of the year and would win writer James Ivory his first Oscar. To follow this, Guadagnino would release Suspiria, a remake of the Argento horror classic that is an hour longer and expands the story and the body horror to exponential proportions. It was incredibly divisive and controversial, a bold follow-up unexpected of someone who previously directed a best picture nominated film.

Now in 2024, Guadagnino has repeated what he did less than a decade prior. Challengers became one of the most talked about movies of the year directly after its theatrical release, and is truly one of the most visionary films to be released in quite a while. Now Guadagnino brings audiences Queer, adapted from the William S. Burroughs novel of the same name, a surreal and audacious character portrait that has been garnering a Last Temptation of Christ-like reaction from audiences.

Queer is many things: a straightforward Burroughs adaptation, a crazed gay odyssey, a destructive character study, a reaction to Call Me By Your Name. But mostly Queer, like Suspiria and Challengers, is a cinematic vessel for Guadignino and his collaborators to push form as far as they can to achieve a transformed vision of cinema. The argument of “the future of cinema” has been one present in film-goers minds this past decade. If we are to argue for who is pushing it further I would throw Guadagnino’s name into the ring. Of these two 2024 films by Guadagnino, Challengers is by far the more exemplary film. But Queer is the more fascinating of the two, and will be seen as Guadagnino’s One From the Heart in decades to come.

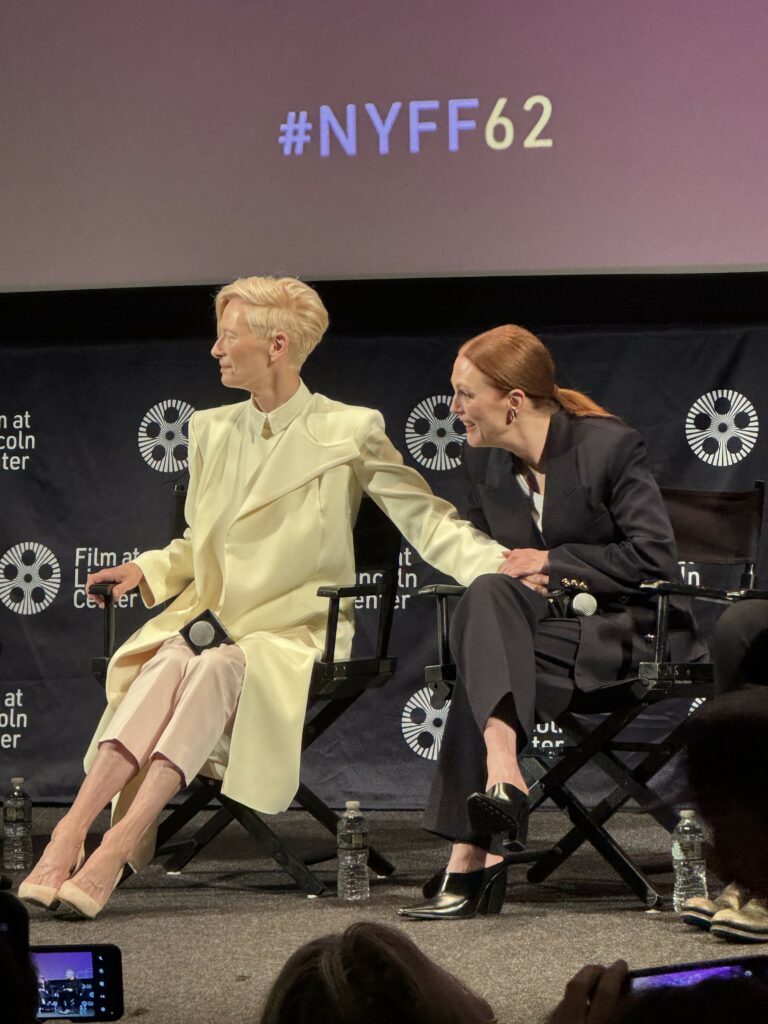

THE ROOM NEXT DOOR (Pedro Almodovar, 107m):

Like Schrader’s Oh, Canada; Almodovar’s first English language feature, The Room Next Door, is a film about mortality; not just in the singular but on a global scale. Tilda Swinton plays a former war journalist dying of cancer, who enlists her friend Julianne Moore to be present with her when she takes her own life via cyanide pill. As someone who is not a fan of Almodovar’s films, The Room Next Door is a surprisingly wonderful entry in his filmography. His colorful stylings are ever so present–note the audience member who afterwards remarked, “It’s nice to see a film with color again.”

Like Schrader’s Oh, Canada; Almodovar’s first English language feature, The Room Next Door, is a film about mortality; not just in the singular but on a global scale. Tilda Swinton plays a former war journalist dying of cancer, who enlists her friend Julianne Moore to be present with her when she takes her own life via cyanide pill. As someone who is not a fan of Almodovar’s films, The Room Next Door is a surprisingly wonderful entry in his filmography. His colorful stylings are ever so present–note the audience member who afterwards remarked, “It’s nice to see a film with color again.”

The parts of his films that irk me are also present. The soap opera style character melodrama never feels raw and true like Sirk or Fassbinder. But in Swinton, Moore, and John Turturro, playing a former lover of both characters, Almodovar finds a grounded performance amidst his melodramatic style. There are extraordinary dialogues and allusions to James Joyce that question the fate of our existence; what it means to live and what it means to die. This might be his finest film for me, but for others it may blend in into his back catalog.